DRC moves to monopolise about 25 percent of all cobalt exports

The Democratic Republic of Congo, the world’s biggest producer of cobalt, created a state monopoly that will buy all output not extracted by industrial operators in a bid to exert more control over the price of the key ingredient in rechargeable batteries.

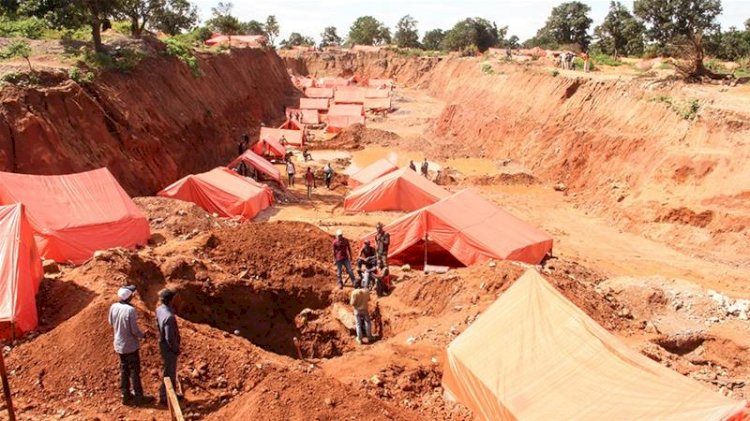

The central African nation dominates output of the metal, accounting for more than 70% of the global market in 2018. While most Congolese cobalt comes from large, mechanized mines operated by companies including Glencore Plc, artisanal miners can account for as much as a quarter of the nation’s output.

The move to control “the whole value chain of the artisanal sector” arises from the country having “insufficient control” over the metal’s price despite its “strategic position” in the market, states a decree signed by Prime Minister Sylvestre Ilunga and Mines Minister Willy Kitobo Samsoni on Nov. 5.

The purchases will be made by a company controlled by state-owned miner Gecamines, and it will be responsible for processing cobalt ores bought from authorized artisanal miners, according to the decree. The unit will retain the monopoly for five years and has the option of renewing the arrangement.

While Gecamines doesn’t have significant processing capacity, the decree authorizes the monopoly to exercise its rights “directly or through partnerships or by delegating all or part of its activity to one or more other companies.”Cobalt is exported from Congo in semi-finished form as concentrate or hydroxide.

The decree covers all artisanal production of minerals that Congo declared “strategic” in 2018, including coltan and cobalt. Exporters pay a 10% royalty on these minerals. As Gecamines isn’t active in the coltan-producing area of Congo, it isn’t clear how the decree will be implemented there.

A separate decree, also signed on Nov. 5, established a regulator whose tasks include ensuring that no children are active on mining sites. The orders gave artisanal mining cooperatives a 60-day deadline, which expired earlier this month, to obtain certificates from the new body and comply with the monopoly. However, neither the regulator nor the company have started operating.

Kitobo, Ilunga’s spokesman Albert Lieke, and Gecamines Chairman Albert Yuma and Director-General Jacques Kamenga didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Artisanal output soared when the cobalt price rallied in 2017 and early 2018, providing as much as 20% of Congo’s production, according to metals trader Darton Commodities. Congolese officials put the figure as high as 30%, while an estimated 200,000 people make a living digging copper and cobalt in the Katanga region, according to Trafigura Group Ltd., the Singapore-based commodities trading and logistics company.

The Congolese measures could impact artisanal cobalt’s role as the “swing producer” in the global market, said George Heppel, senior analyst at business intelligence firm CRU Group.

Even though Congo is most likely to exercise its buying rights when prices are high, “we don’t think the government can get material to market as efficiently” as the mainly Chinese traders do, Heppel said. This could “hinder the ability of artisanal mining to balance the market.”